The United States Constitution is unusually difficult to amend. As spelled out in Article V, the Constitution can be amended in one of two basic ways. First, amendment can take place by a vote of two-thirds of both the House of Representatives and the Senate followed by a ratification of three-fourths of the various state legislatures or conventions in three-fourths of the states (ratification by thirty-eight states would be required to ratify an amendment today). This first method of amendment is the only one used to date, and in all but the case of the 21st Amendment, state ratification took place in legislatures rather than state conventions. Second, the Constitution might be amended by a Convention called for this purpose by two-thirds of the state legislatures, if the Convention's proposed amendments are later ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures (or conventions in three-fourths of the states).

Because any amendment can be blocked by a mere thirteen states withholding approval (in either of their two houses), amendments don't come easy. In fact, only 27 amendments have been ratified since the Constitution became effective, and ten of those ratifications occurred almost immediately--as the Bill of Rights. The very difficulty of amending the Constitution greatly increases the importance of Supreme Court decisions interpreting the Constitution, because reversal of the Court's decision by amendment is unlikely except in cases when the public's disagreement is intense and close to unanimous. Even unpopular Court decisions (such as the Court's protection of flagburning) are likely to stand unless the Court itself changes its collective mind.

The Court has at various times considered the validity of constitutional amendments. Importantly, the Court has considered the method of proposal and ratification, as well as the constitutionality of the subject matter of the amendment, to be a justiciable--and, therefore, not a "political"--question. In the Hawke v Smith (1920), for example, the Court upheld Ohio's ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment over objections that the Ohio Constitution provided for a referendum on the issue by voters that might have overridden the Ohio legislature's ratification of the amendment. The Court concluded that the federal law set for in Article V providing specifically for ratification by state legislatures preempted conflicting state procedures for ratification. Also, in the National Prohibition Cases (1920), the Court generally upheld the validity of the Eighteenth Amendment, rejecting arguments that a prohibition on the distribution and possession of alcohol was a constitutionally impermissible subject matter for a constitutional amendment.

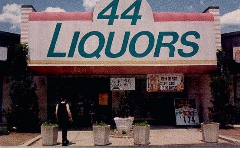

Two more recent cases included in our readings consider the effect of the Twenty-First Amendment repealing the Eighteenth Amendment. In the first case, LaRue v California (1972), the Court concludes that the Twenty-First Amendment qualifies the First Amendment, thus allowing states to regulate expression in establishments that serve alcohol, even when such restrictions might violate the First Amendment if applied elsewhere. In 1996, however, in the 44 Liquormart, Inc. v Rhode Island, the Court disavows its earlier conclusion and makes clear that the Twenty-First Amendment, while it may allow restrictions on alcohol that would otherwise violate the Commerce Clause, in no way qualifies the reach of the First Amendment. The Court therefore concludes that Rhode Island's restrictions on advertising the price of alcohol violate the First Amendment.

In 2005, in Granholm v Heald , the Court held that Section 2 of the 21st Amendment did not give states the power to discriminate against out-of-state wine sellers in ways that would otherwise violate the Commerce Clause. Ruling 5 to 4, the Court struck down a Michigan law banning out-of-state wineries from selling wine to Michigan residents over the Internet. Michigan allowed Michigan wineries to directly ship to consumers, but prohibited non-Michigan wineries from doing the same. The Court noted, however, that the 21st Amendment clearly gave the state the power to ban ALL direct shipments of wine (or other alcoholic beverages) to consumers if it chose to do so. Four dissenters argued that the history of the 21st Amendment proved that it was meant to exclude regulation of alcoholic beverages from the normal prohibitions on state discrimination under the Commerce Clause--however misguided that policy might seem today.

1. Is it a good thing that our Constitution is so difficult to amend? Why should a minority be able to frustrate a clear majority's wish to alter the Constitution?

2. Don't the amendment procedures doom many potentially good changes, because one or the other political parties will see itself as adversely affected by a proposed change? For example, won't Republicans forever block Washington D.C. from gaining representation in Congress because any representative elected by D. C. citizens is likely to be a Democrat? Isn't it equally unlikely that the electoral college method of choosing a president will ever be changed?

3. May a state rescind its prior ratification if an amendment has yet to be ratified by three-fourths of the states?

4. Many proposed amendments, such as the Equal Rights Amendment, have limited the period for ratification to seven years? Are such limits a good idea? What if a state ratifies an amendment after the specified period? What if a proposed amendment contained no time limit and was ratified two centuries later (see the 27th Amendment)?

5. The Court has recognized the constitutionality of ratification procedures as a justiciable question. Should the Court consider these issues, or should it leave them to the other branches to work out?

6. Only two provisions in the Constitution have been made unamendable--and the unamendability of one of those, the provision barring restrictions on the importation of slaves, expired in 1808. The only provision now unamendable is the guarantee that each state will have equal suffrage in the Senate. Why do you suppose the framers attached such importance to that provision? What if--despite the provision against changing suffrage in the Senate--, we first repealed the provision prohibiting amendment and that ratified an amendment giving larger states more Senate representation? Are there other impliedly unamendable provisions? Could we abolish the Executive Branch by amendment?

7. What if an amendment (say, an amendment prohibiting abortions) included language prohibiting the amendment from ever being repealed? Should the courts enforce the provision and invalidate an amendment that sought to again permit abortions?

8. The Court, in LaRue and 44 Liquormart, wrestled with the question of whether the Twenty-First Amendment qualified the First Amendment. What do you think is the best answer to that question?

9. Consider the various proposed, but unratified, amendments listed on the U. S. Constitution Online link (below). Which of these proposed amendments do you think should have been adopted?

Link

U. S. Constitution Online: Constitutional Amendments

This site contains a listing of proposed, but unratified amendments as well as a listing of proposed amendments which have recently been introduced in Congress.

National Prohibition Cases (1920)

Hawke v Smith (1920)

Larue v California (1972)

44 Liquormart, Inc. v Rhode Island (1996)

Granholm v Heald (2005)

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments,

which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress; Provided that no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article*; and that no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.

* Art. I, Sec. 9, clause 1: The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight.

Art. I, Sec. 9, clause 4: No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken.

On the eve of Prohibition in 1920, a mournful toast is raised around John Barleycourn's coffin.

44 Liquormart took its challenge to Rhode Island's restrictions on advertising alcohol prices to the Supreme Court.

(photo:ABA Journal)

Passed by Congress December 18, 1917. Ratified January 16, 1919.

Section 1.

After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Section 2.

The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Passed by Congress February 20, 1933. Ratified December 5, 1933.

Section 1.

The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.

Section 2.

The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or Possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.